Imagine standing amidst a landscape that seems plucked from mythology—massive granite boulders stacked impossibly upon each other, creating surreal formations that dwarf the human scale. Between these ancient stones lie the scattered remnants of what was once the world’s second-largest city after Beijing, a metropolis so wealthy that foreign travelers called it “one of the most beautiful cities” they had ever seen. Welcome to the Hampi ruins, where the magnificent Vijayanagara Empire’s glory still echoes through over 1,600 surviving monuments spread across 4,100 hectares of otherworldly terrain.

The Hampi ruins tell one of history’s most dramatic stories—of an empire that ruled South India for over two centuries, amassed unimaginable wealth, built architectural marvels that still astound engineers today, and then fell spectacularly in a single devastating battle that left its capital pillaged and abandoned. Today, this UNESCO World Heritage Site stands as a hauntingly beautiful testament to human ambition, artistic achievement, and the impermanence of even the mightiest civilizations.

Whether you’re a history enthusiast drawn to tales of forgotten empires, an architecture lover fascinated by ancient engineering marvels, a photographer seeking surreal landscapes unlike anywhere else on Earth, a spiritual seeker exploring India’s sacred geography, or an adventurer wanting to explore one of Asia’s most spectacular archaeological sites, the Hampi ruins offer an experience that transcends ordinary tourism—a journey through time that will fundamentally alter your understanding of India’s cultural richness and historical depth.

The Rise of Vijayanagara: From Ashes to Glory

Every great empire has its founding myth, and the story of Vijayanagara and the subsequent Hampi ruins we see today begins with destruction, devotion, and remarkable vision.

The Fall of Kampili and Seeds of Empire

In the early 14th century, the Deccan plateau of South India was a patchwork of kingdoms constantly threatened by invasions from Delhi Sultanate armies pushing southward. The Kampili kingdom, located in present-day northern Karnataka, stood as one of the last Hindu strongholds resisting Muslim expansion into South India.

In 1327, the armies of Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi, besieged Kampili’s capital, which stood approximately 33 kilometers from what would become Hampi. As defeat became inevitable, the kingdom’s soldiers prepared for a final stand while the women of the royal court performed jauhar—ritual mass suicide to avoid capture and dishonor. The Kampili kingdom fell, its royal line ended, and the region came under Delhi Sultanate control.

Among the Kampili army survivors were two brothers, Harihara and Bukka, who would transform this catastrophic defeat into the foundation of South India’s greatest empire. According to historical accounts, these brothers were captured and taken to Delhi, where they were converted to Islam and employed in the Sultanate’s service. However, their hearts remained in their homeland and with their original faith.

The Vision of Vidyaranya and the Birth of an Empire

Around 1336, Harihara and Bukka managed to escape Delhi and return to their homeland in the Tungabhadra River region. Here, they met Sage Vidyaranya, a revered Hindu scholar and spiritual leader from the powerful Sringeri Sharada Peetham monastic order. Vidyaranya had a grand vision—to establish a strong Hindu kingdom that could resist further Islamic invasions and protect South Indian culture, temples, and traditions.

Under Vidyaranya’s guidance and blessings, the brothers reconverted to Hinduism and founded the Vijayanagara Empire in 1336. The empire’s name, meaning “City of Victory,” reflected both their triumph over adversity and their determination to protect dharma (righteous duty) against external threats.

The brothers chose Hampi as their capital for strategic and spiritual reasons. The location, on the south bank of the Tungabhadra River, offered natural protection—surrounded by rocky hills providing excellent defensive advantages. Additionally, the site had ancient religious significance, mentioned in Hindu texts as Pampa Kshetra, associated with goddess Pampa and believed to be the mythical Kishkindha where Lord Rama met Hanuman in the Ramayana epic. This connection to sacred geography lent spiritual legitimacy to their new empire.

The Empire’s Spectacular Growth

What began as a small kingdom around Hampi rapidly expanded under successive rulers into one of South India’s most powerful empires. The Vijayanagara Empire at its peak controlled virtually all of peninsular India south of the Krishna River—encompassing most of modern-day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, as well as parts of Goa and Maharashtra.

The empire’s military prowess was legendary. Historical records describe armies numbering over one million soldiers, including cavalry, infantry, and war elephants. This massive military machine successfully repelled numerous invasions from the Bahmani Sultanate and later the Deccan Sultanates for over two centuries—an achievement that earned Vijayanagara the title of “the last great Hindu kingdom.”

But military might alone doesn’t explain Vijayanagara’s success. The empire’s rulers were remarkably tolerant and cosmopolitan for their era. While they championed Hindu culture and built magnificent temples, they also employed Muslims in high administrative and military positions, welcomed foreign traders regardless of religion, and patronized diverse artistic and architectural traditions. This openness created a cultural melting pot that attracted merchants, artists, scholars, and travelers from across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

The Golden Age Under Krishnadevaraya

The Vijayanagara Empire reached its zenith under Krishnadevaraya (r. 1509-1529), considered one of the greatest rulers in Indian history. A brilliant military strategist, accomplished poet, patron of arts, and effective administrator, Krishnadevaraya expanded the empire to its greatest territorial extent and transformed Hampi into a dazzling capital that rivaled any city in the world.

Contemporary accounts from Portuguese and Persian travelers describe Vijayanagara-Hampi during Krishnadevaraya’s reign in almost mythical terms:

- The city stretched for miles, with elaborate fortifications featuring seven concentric defensive walls

- The bazaars were so long that a person could barely see from one end to the other

- Merchants from Persia, Portugal, China, Africa, and Arabia conducted business in dozens of languages

- The royal treasury overflowed with gold, diamonds, rubies, and pearls

- The palace complex featured decorated halls, audience chambers, pleasure gardens, and luxurious zenana (women’s quarters)

- Temples were adorned with gold and precious gems

- The streets were clean, well-organized, and safer than European cities of the same era

Krishnadevaraya himself was a poet who wrote in multiple languages, a warrior who never lost a battle, and a visionary who understood that a great empire needed both military strength and cultural sophistication. His patronage attracted the finest artists, architects, musicians, dancers, and scholars to Hampi, creating a golden age of South Indian art and literature that influenced regional culture for centuries to come.

The Catastrophic Fall: Battle of Talikota

Tragically, Vijayanagara’s glory ended suddenly and violently. By the mid-16th century, the Bahmani Sultanate had fragmented into five independent Deccan Sultanates (Bijapur, Golconda, Ahmednagar, Bidar, and Berar). Despite their constant internal conflicts, these sultanates shared one common concern—the powerful Hindu empire to their south.

In 1565, the five sultanates formed an unprecedented alliance with a single goal: destroy Vijayanagara. The massive combined army, possibly numbering 500,000 soldiers, marched south to meet Vijayanagara forces at Talikota in northern Karnataka on January 23, 1565.

The Vijayanagara army, though also massive and battle-tested, faced several disadvantages. The elderly regent Rama Raya, who ruled in place of the weak emperor Sadasiva Raya, commanded the forces. More critically, the sultanates employed superior artillery and firearms, relatively new military technologies that Vijayanagara had been slower to adopt.

The battle initially favored Vijayanagara, with their war elephants and cavalry pushing back the sultanate forces. Victory seemed within grasp until disaster struck—two Muslim generals in the Vijayanagara army, the mercenary Gilani brothers according to some accounts, suddenly switched sides and joined the sultanates. This treacherous move created chaos in Vijayanagara ranks.

The sultanate forces quickly capitalized on the confusion, capturing Rama Raya and beheading him. His severed head was stuffed with straw and paraded before both armies. The sight of their commander’s head destroyed Vijayanagara morale. The army collapsed into panicked retreat, suffering devastating casualties.

The Pillaging of Hampi

What followed was one of history’s most thorough destructions of a capital city. The victorious sultanate armies marched to Hampi and systematically pillaged it for six months. They looted the palaces, temples, and treasury, carrying away unimaginable wealth. More tragically, they deliberately destroyed much of the city’s cultural heritage:

- Temple towers and sanctums were desecrated or demolished

- Massive stone sculptures were smashed or defaced

- Buildings were set ablaze

- The irrigation systems and water infrastructure were destroyed

- Libraries and manuscripts were burned

The destruction was so complete that Hampi was abandoned shortly after. The surviving members of the royal family fled south and attempted to reestablish the empire at Penukonda and later other locations, but Vijayanagara never recovered its former glory. The empire limped along in diminished form until finally dissolving completely in 1646.

When Italian merchant Cesare Federici visited Hampi a few decades after its fall, he wrote: “the citie of Bezeneger (Hampi-Vijayanagara) is not altogether destroyed, yet the houses stand still, but emptie, and there is dwelling in them nothing, as is reported, but Tygres and other wild beasts.” The magnificent capital had become a ghost city haunted by memories of its vanished glory.

The UNESCO World Heritage Site: Understanding Hampi Ruins Today

The Hampi ruins we see today represent both the triumph of human creativity and the tragedy of destruction. In 1986, UNESCO designated Hampi as a World Heritage Site, recognizing its “outstanding universal value” and describing it as an “austere, grandiose site” that bears “exceptional testimony to the vanished civilization of the kingdom of Vijayanagara.”

The Scale and Scope

The Hampi ruins encompass an enormous area—4,187.24 hectares (approximately 41.87 square kilometers or 16 square miles) of protected heritage site. To put this in perspective, that’s larger than many small cities and contains over 1,600 surviving structures, including:

- Temples ranging from small shrines to massive complexes

- Royal palaces and administrative buildings

- Pavilions (mandapas) used for ceremonies and gatherings

- Fortifications including seven concentric walls (mostly ruined)

- Gateways and checkposts controlling access to different zones

- Elephant stables and horse stables

- Treasury buildings

- Queen’s quarters and royal women’s enclosures

- Market streets with pillared arcades

- Stepped water tanks (pushkaranis) and elaborate irrigation systems

- Aqueducts and water channels

- Memorial structures and victory pillars

Remarkably, despite the systematic destruction in 1565 and 450+ years of exposure to elements, many structures remain in excellent condition. The Vijayanagara builders’ use of extremely hard local granite proved both blessing and curse—while it made the monuments nearly indestructible, allowing them to survive centuries, it also made them resistant to the sultanates’ destruction attempts, preserving the evidence of their deliberate vandalism.

The Unique Landscape

What makes the Hampi ruins particularly special is their spectacular natural setting. The site is characterized by a surreal landscape of massive granite boulders—some balanced precariously on each other in seemingly impossible configurations, others scattered across plains and hillsides like discarded toys of giants.

Geologists explain that these formations resulted from millions of years of weathering of a massive granite batholith. The rounded, exfoliated boulders create an otherworldly atmosphere that perfectly complements the historical ruins. Many early travelers and modern visitors describe feeling transported to another planet or into a fantasy realm when first encountering Hampi’s landscape.

The Tungabhadra River flows along the northern edge of the site, providing the water resources that made this location viable for a major city. The river valley’s fertile soil supported extensive agriculture, while the rocky hills offered natural defensive positions. This combination of practical advantages and stunning aesthetics made Hampi an ideal imperial capital.

Conservation Challenges and Efforts

Preserving the Hampi ruins presents ongoing challenges. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which manages the site, faces multiple issues:

Natural Weathering: The granite, while hard, still suffers from erosion, particularly from monsoon rains and temperature fluctuations. Salt crystallization and biological growth (lichens, mosses) gradually deteriorate stone surfaces.

Human Impact: With increasing tourism (over 300,000 visitors annually pre-pandemic), concerns about visitor impact grow. Climbing on monuments, touching carvings, littering, and general wear-and-tear from foot traffic all contribute to deterioration.

Illegal Quarrying: Granite quarrying in areas surrounding the protected zone has damaged the landscape and threatens lesser-known monuments outside the core zone.

Development Pressure: The growing modern town of Hampi and nearby Hospet city create pressure for development that conflicts with conservation goals.

Limited Resources: Like many archaeological sites in India, Hampi suffers from insufficient funding, staffing, and resources for optimal maintenance and research.

Despite these challenges, significant conservation work continues. ASI has undertaken stabilization of collapsing structures, documentation of inscriptions, creation of visitor management plans, and research into the site’s history and architecture. International organizations and experts also contribute technical expertise and funding for specific projects.

Research and Rediscovery

The scholarly rediscovery of Hampi began in the 19th century when British colonial archaeologists and historians started studying the ruins. Alexander Rea’s surveys in the 1880s and Robert Sewell’s landmark 1900 publication “A Forgotten Empire” brought Hampi to international scholarly attention.

In the 1980s and 1990s, comprehensive research by international teams led by John M. Fritz and George Michell revolutionized understanding of Vijayanagara’s urban planning, architecture, and society. Using archaeological surveys, excavations, analysis of historical texts, and architectural studies, these researchers reconstructed how the ancient city functioned, revealing sophisticated urban planning principles that governed its development.

Their work demonstrated that Vijayanagara wasn’t just a random collection of buildings but a carefully planned city with distinct zones—sacred centers around major temples, royal quarters, administrative areas, specialized markets, residential neighborhoods, and agricultural zones—all connected by a sophisticated road network and water distribution system.

Ongoing excavations continue to reveal new discoveries. Recent work has uncovered:

- Previously unknown palace complexes and structures

- Evidence of extensive international trade connections

- Buddhist sculptures indicating the site’s pre-Vijayanagara importance

- Details of daily life through artifacts like ceramics, tools, and ornaments

- Advanced hydraulic engineering systems for water management

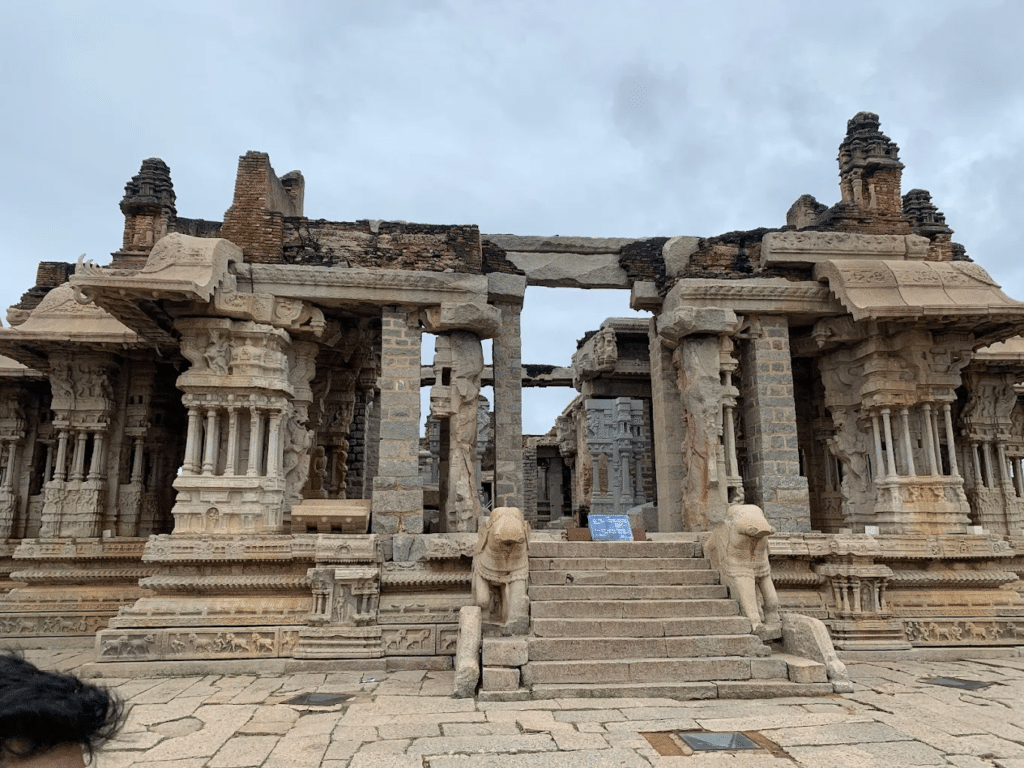

Vittala Temple Complex: The Pinnacle of Vijayanagara Architecture

Among the hundreds of monuments in the Hampi ruins, the Vittala Temple Complex stands supreme—representing the absolute pinnacle of Vijayanagara artistic and architectural achievement. Located about 2 kilometers from the main Hampi bazaar area, on the banks of the Tungabhadra River, this temple complex showcases the empire’s builders at their most ambitious and inspired.

History and Dedication

The Vittala Temple was constructed over several decades during the 15th and early 16th centuries. King Devaraya II (r. 1422-1446) initiated construction, dedicating the temple to Lord Vittala (Vithoba), a manifestation of Lord Vishnu particularly revered in Karnataka and Maharashtra. The temple’s construction continued under successive rulers, reaching its final magnificent form during Krishnadevaraya’s reign (r. 1509-1529).

Interestingly, despite being built as a place of worship, the temple apparently never housed regular religious services. Some scholars theorize that the temple was too ornate, too much an architectural showpiece, to function as a traditional place of worship. Others suggest it was designed specifically for royal ceremonies rather than daily rituals. Whatever the reason, the temple’s primary function seems to have been symbolic—a demonstration of Vijayanagara’s wealth, artistic sophistication, and devotion.

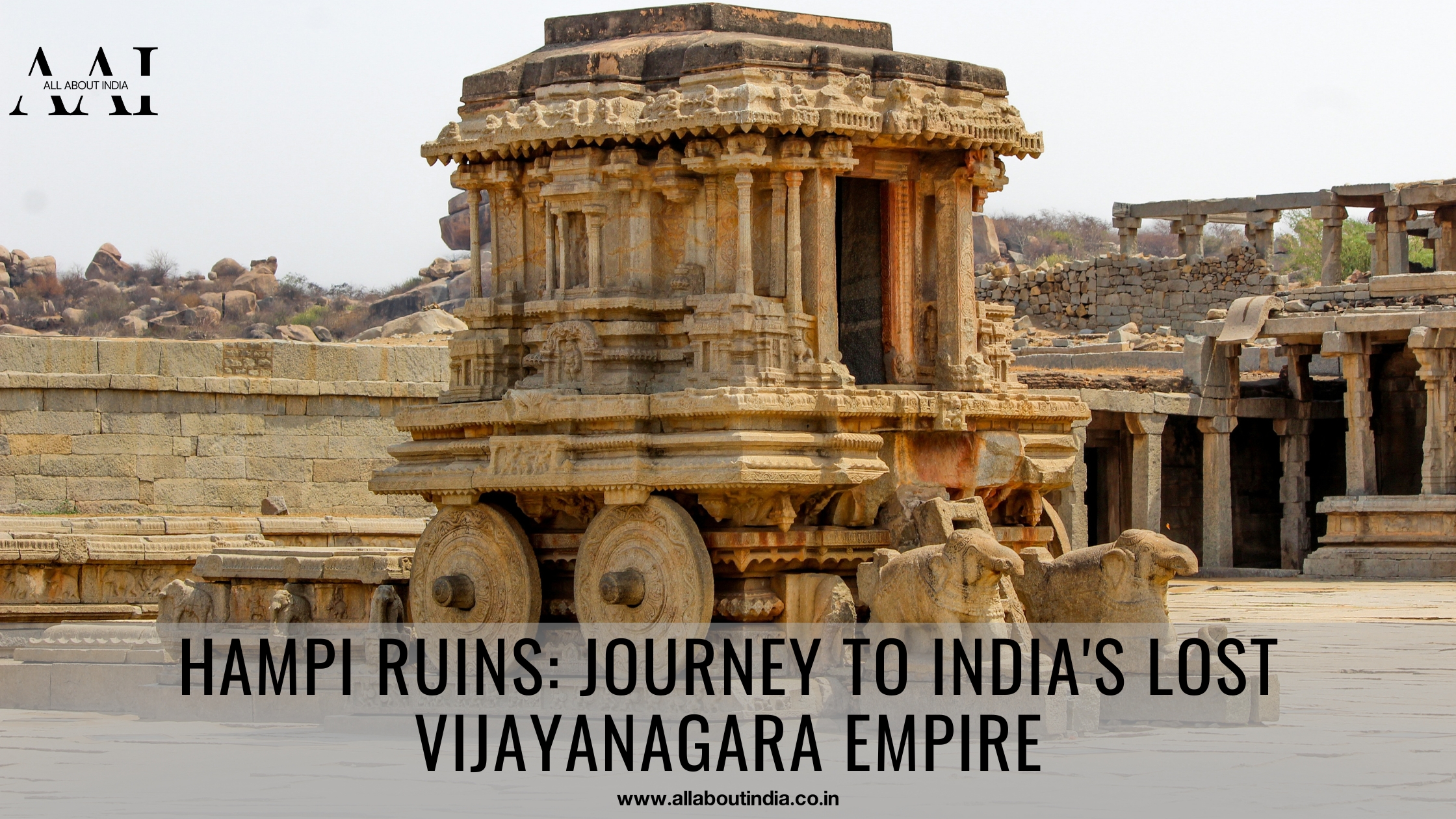

The Magnificent Stone Chariot

The Vittala Temple Complex’s most iconic feature—appearing on countless postcards, book covers, and even India’s old 50-rupee currency note—is the spectacular Stone Chariot. This architectural masterpiece sits in the temple courtyard, a shrine designed in the form of an ornate ceremonial chariot.

Design and Construction: The Stone Chariot stands on a high platform, designed to resemble the wooden ceremonial chariots used in temple festivals to transport deity idols through streets. Every detail of a functional chariot is replicated in stone—wheels with intricate spoke patterns, a covered sanctum where the deity would sit, decorative panels depicting mythological scenes, and even elephant sculptures positioned as if pulling the chariot.

The structure’s technical sophistication is remarkable. While appearing to be carved from a single massive boulder (a monolith), the chariot actually consists of multiple stone blocks so precisely cut and fitted that joints are nearly invisible. This technique required extraordinary skill in stone cutting, structural engineering to ensure stability, and artistic vision to create coherent design across separate elements.

The Wheels: The chariot’s wheels deserve special mention. Each wheel features elaborate floral motifs carved in concentric circles with such precision that they appear almost machine-made. Most remarkably, these wheels were originally functional—they could actually rotate on their stone axles! Visitors in earlier times could turn the wheels, experiencing the incredible feat of creating moving parts from solid granite.

Unfortunately, to prevent damage from excessive handling, authorities eventually locked the wheels, and they no longer rotate. However, examining the wheels closely still reveals the sophisticated engineering that allowed their movement—the axles are slightly smaller than the wheel hubs, and the friction-reducing design of the contact surfaces shows deep understanding of mechanical principles.

The Garuda Shrine: The chariot functioned as a shrine dedicated to Garuda, the divine eagle who serves as Lord Vishnu’s vehicle (vahana) in Hindu mythology. Originally, a Garuda statue sat inside the chariot’s sanctum, but this statue disappeared long ago—either looted during Hampi’s destruction or removed for protection and subsequently lost.

Inspiration from Konark: Historical accounts suggest that Krishnadevaraya conceived the Stone Chariot after seeing the magnificent Sun Temple at Konark in Odisha during a military campaign. Impressed by Konark’s chariot-shaped temple, he apparently commissioned Vijayanagara’s architects to create an even more elaborate version. This story, whether entirely accurate or partly legendary, illustrates the cultural connections and competitive architectural patronage among different Indian kingdoms.

Mythological Carvings: The chariot’s base and walls feature intricate relief carvings depicting scenes from Hindu epics—the Ramayana and Mahabharata—as well as scenes from Krishna’s life. These panels tell stories through stone, with figures carved in such fine detail that expressions, ornaments, and clothing folds are clearly visible despite centuries of weathering.

The Musical Pillars: Stone That Sings

If the Stone Chariot represents the Vittala Temple’s most famous feature, the Musical Pillars constitute its most mysterious and fascinating element. These remarkable pillars, located in the Ranga Mantapa (a large hall within the temple complex), produce musical notes when gently struck—creating melodies from solid granite.

Structure and Design: The Ranga Mantapa contains 56 main musical pillars, each approximately 3-4 feet in circumference. These aren’t simple cylindrical columns but composite structures—each main pillar is surrounded by seven smaller (satellite) pillars arranged in a cluster. The pillars feature elaborate carvings of musicians, dancers, and celestial beings, with intricate detail work covering every surface.

How They Produce Music: The musical pillars’ sonic properties result from precise engineering of the stone’s dimensions, shape, and internal structure. Each cluster of pillars is designed to produce different musical tones:

- When you gently tap different pillars, they emit distinct notes corresponding to musical scales (Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni in Indian classical music notation, or Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti in Western notation)

- The satellite pillars surrounding each main pillar act as resonators, amplifying and modulating the sound

- Different areas of the same pillar produce different tones, allowing for melodic playing

- Together, the pillars can replicate sounds of various musical instruments—drums, cymbals, stringed instruments, bells, and more

The acoustic engineering required to achieve this is extraordinary. The builders needed to understand:

- How stone’s density, shape, and dimensions affect resonance

- Mathematical relationships between pillar measurements and musical intervals

- Acoustic properties of the hall’s architecture to enhance sound

- How to consistently replicate these properties across dozens of pillars

The British Experiment: The musical pillars’ remarkable properties attracted intense curiosity from British colonial officials and engineers in the 19th century. Unable to accept that solid stone could produce musical notes without some hidden mechanism, they decided to investigate. British officials ordered two pillars to be cut open to discover the “secret” inside.

To their likely embarrassment, they found nothing—just solid granite throughout. The pillars’ musical properties resulted purely from their precise shape, dimensions, and the granite’s natural acoustic characteristics. The two damaged pillars remain visible in the temple today, serving as silent testimony to this misguided investigation and as a reminder that ancient Indian builders possessed sophisticated scientific and engineering knowledge that even seemed magical to later observers.

Preservation Concerns: Today, touching the musical pillars is prohibited to prevent wear and damage. While this disappoints visitors who would like to experience the acoustic phenomenon firsthand, it’s necessary for preservation. Decades of countless visitors tapping the pillars caused visible wear on the stone surfaces. The prohibition has sparked debates about balancing heritage preservation with allowing experiential engagement with historical sites.

Some authorized demonstrations by guides using gentle taps on permitted pillars allow visitors to hear the phenomenon, albeit in limited form. These controlled demonstrations give a glimpse of what ancient temple visitors would have experienced when these pillars were freely accessible.

Other Architectural Marvels in the Complex

The Maha Mantapa (Great Hall): The temple‘s main hall showcases the absolute pinnacle of Vijayanagara architectural ornamentation. This massive structure sits on an elaborately decorated raised platform (adhishthana) featuring intricate carvings of horses, warriors, elephants, mythological creatures, and geometric patterns in multiple registers.

The mantapa’s pillars are masterworks of sculpture—no two are identical, each featuring unique carved designs of rearing yalis (mythical lion-like creatures), horses, elephants, and composite beasts. The pillars’ capitals showcase makara (mythical aquatic creatures) motifs and ornate bracket figures. The ceiling features carved lotus flowers and geometric patterns.

What’s particularly remarkable is the scale—the Maha Mantapa’s pillars reach impressive heights while maintaining extraordinary detail in their carvings. The engineering required to quarry, transport, shape, carve, and erect these massive granite pillars with such precision demonstrates remarkable organizational capability and technical skill.

The Kalyana Mantapa (Marriage Hall): This ornate pavilion, located in the southeastern part of the temple complex, served for ceremonial functions including symbolic divine marriages. The structure features beautifully carved pillars, decorative friezes, and an overall design that creates a sense of celebration and festivity appropriate to its function.

The Utsava Mantapa (Festival Hall): Another pavilion used during temple festivals and special ceremonies, the Utsava Mantapa’s design emphasizes open spaces for gathering large crowds while maintaining architectural beauty through carved pillars and decorative elements.

The Pushkarani (Sacred Tank): The temple complex includes a large stepped water tank located to its east. This pushkarani features symmetrical steps descending to the water on all four sides, with a small mantapa (pavilion) at its center that was used for religious ceremonies. The tank’s geometric precision and the quality of stone cutting in its steps demonstrate the builders’ attention to functional structures, not just decorative temples.

The Temple Gopurams: Three towering gateway towers (gopurams) mark entrances to the temple complex from the east, north, and south. These gopurams were commissioned by two of Krishnadevaraya’s queens in 1513 CE. Though now mostly ruined, their remaining portions and scattered architectural fragments hint at their original magnificence. These gateways would have featured multiple tiers of carved figures, creating decorated towers that announced the temple’s importance from considerable distances.

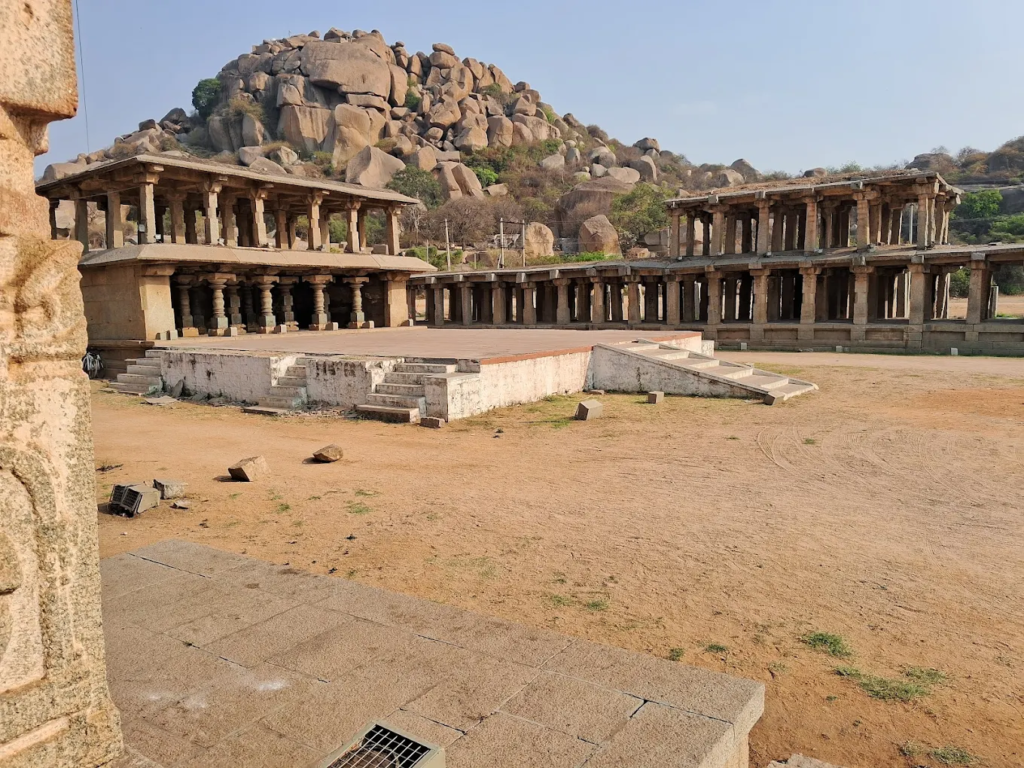

The Vittala Temple Bazaar Street

Extending eastward from the Vittala Temple is a long, broad street lined with the ruins of pillared pavilions (mandapas) on both sides. This was the temple’s market street, where vendors would sell flowers, offerings, food, and goods during temple festivals and daily commerce.

The street’s regularity and the uniformity of the pavilion structures indicate planned urban design. Each pavilion features a row of carved pillars supporting a roof (now mostly collapsed), creating covered walkways that protected merchants and shoppers from sun and rain.

Walking this ancient market street today, with its empty pavilions stretching into the distance and granite boulders rising on either side, creates a profound sense of connection to the past. You can almost hear the ancient crowds, smell the incense and flowers, and see the colorful fabrics that once filled these now-silent arcades.

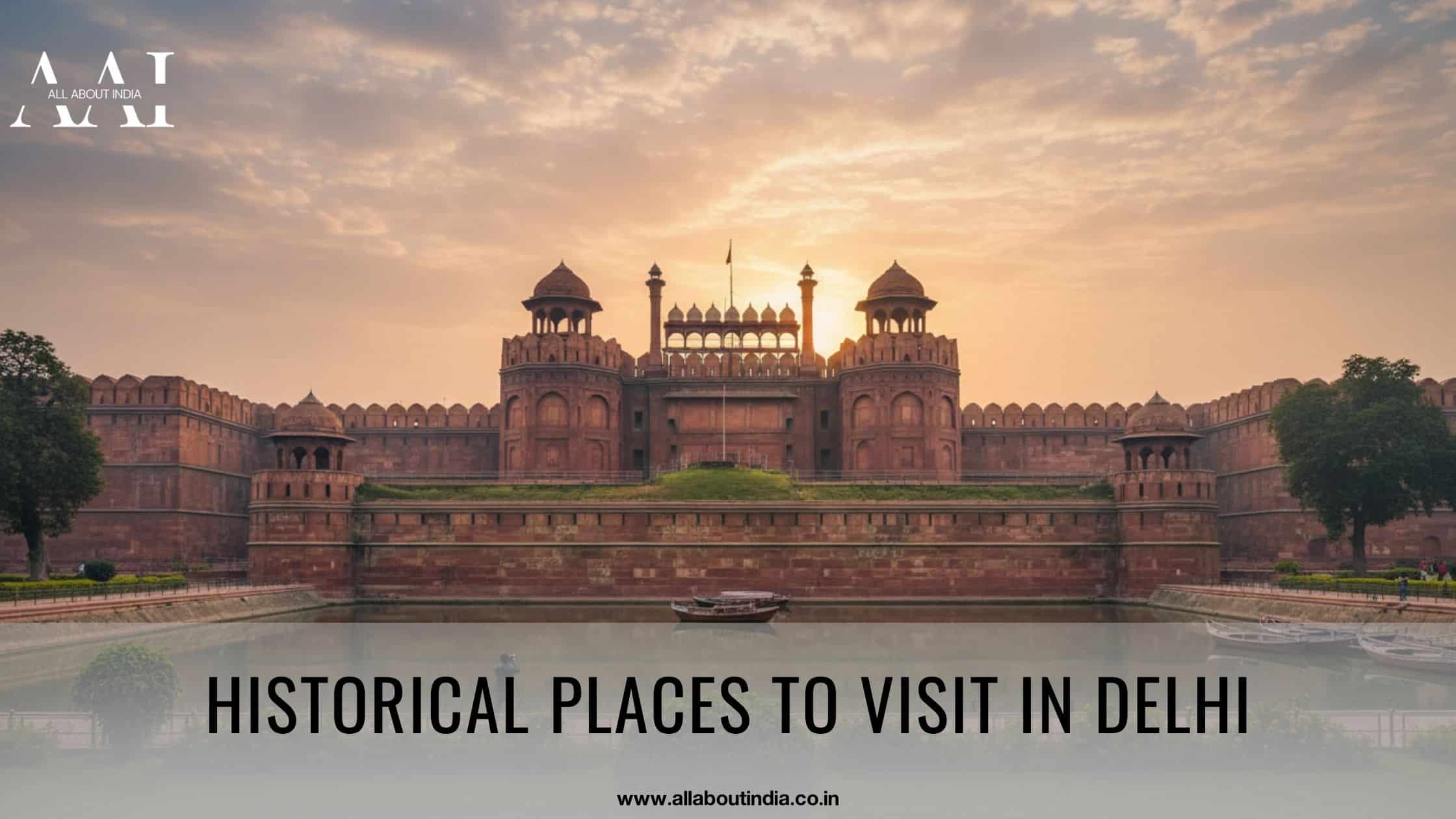

The Sacred Center: Virupaksha Temple and Hampi Bazaar

While the Vittala Temple represents Vijayanagara’s architectural zenith, the Virupaksha Temple constitutes the Hampi ruins’ spiritual heart—and remarkably, unlike most of Hampi’s monuments, it remains an active place of worship today, maintaining religious traditions unbroken for over 1,300 years.

Ancient Origins

The Virupaksha Temple’s history predates the Vijayanagara Empire by centuries. The site has been sacred to Lord Shiva (worshipped here as Virupaksha, “he whose eyes are Shiva”) since at least the 7th century CE, with inscriptions and architectural remains indicating continuous religious activity at this location for over a millennium before Vijayanagara’s founders arrived.

This ancient sanctity made the site ideal for the new empire’s religious center. The Vijayanagara rulers didn’t build a new temple on virgin ground—they expanded, embellished, and monumentalized an already sacred space, connecting their new empire to ancient spiritual traditions and legitimizing their rule through association with timeless devotion.

Architecture and Expansion

The core temple, containing the sanctum sanctorum (garbhagriha) where the Shiva lingam resides, dates to before the Vijayanagara period. The empire’s rulers, particularly Krishnadevaraya, added extensive structures that transformed a modest shrine into a massive temple complex:

The Towering Gopuram: The temple’s eastern entrance gopuram (gateway tower) is Hampi’s tallest structure, standing approximately 50 meters (165 feet) high with nine tiers. Constructed in 1442 during the reign of Devaraya II, this gopuram dominates Hampi’s skyline and serves as a landmark visible from across the ruins.

The gopuram’s tiers diminish in size as they rise, creating a pyramidal silhouette typical of South Indian temple architecture. Each tier features carved figures of deities, mythological beings, and decorative elements, though many are now weathered or damaged. The tower’s sheer scale required remarkable engineering—supporting such weight while maintaining stability through centuries of earthquakes, monsoons, and general weathering demanded sophisticated structural knowledge.

The Ranga Mantapa: This pillared hall, added during Krishnadevaraya’s reign in 1510 CE, features elaborately carved pillars depicting scenes from mythology and royal life. The hall connects to the temple’s inner courtyard and was used for religious ceremonies, musical performances, and gatherings.

The Kalyana Mantapa: Another elegant pillared hall used for ceremonial occasions, featuring intricate carvings and an elevated platform.

The Temple Kitchen Complex: The temple includes extensive kitchen facilities capable of preparing food for thousands of devotees during festivals. Even today, the temple operates these kitchens during major celebrations, maintaining traditions centuries old.

The Massive Nandi: Opposite the temple, at the end of the Hampi Bazaar street, sits an enormous monolithic Nandi (Shiva’s sacred bull vehicle) measuring about 3 meters tall. This perfectly proportioned sculpture was carved from a single boulder and polished to a smooth finish.

The Living Temple

What makes the Virupaksha Temple unique among the Hampi ruins is its continued religious life. While most of Hampi’s structures are dead archaeological monuments, the Virupaksha Temple remains a vibrant place of worship:

- Daily pujas (worship ceremonies) are conducted multiple times

- The temple employs priests who maintain traditional rituals

- Devotees from across India visit to offer prayers and seek blessings

- Major Hindu festivals (Mahashivratri, Ugadi, etc.) are celebrated with traditional fervor

- The temple’s chariot (rath) is processed through streets during annual festivals

- Pilgrims consider bathing in the nearby Tungabhadra River sacred before temple visit

This living tradition creates a powerful connection between past and present. The same rituals performed today were conducted during Vijayanagara times—the same chants, the same offerings, the same devotion spanning over 500 years of continuous practice.

Hampi Bazaar: The Ancient Market Street

Extending directly east from the Virupaksha Temple is Hampi’s longest and most impressive ancient street—the Hampi Bazaar. This broad avenue, lined on both sides with ruined pavilions, stretches approximately 1 kilometer from the temple gopuram to the monolithic Nandi.

During Vijayanagara times, this was one of the city’s main commercial streets, thronged with merchants, pilgrims, residents, and visitors. The pavilions housed shops selling everything from silk and spices to jewelry and religious articles. Some pavilions served as residences for wealthy merchants or rest houses for travelers.

Historical accounts describe the Hampi Bazaar as a place of incredible activity and diversity:

- Merchants from Persia, Arabia, China, and Europe conducted business

- Courtesans (devadasis) performed traditional dances in some pavilions

- Money changers exchanged currencies from different kingdoms

- Jewelers created intricate ornaments from gold and precious stones

- Weavers displayed silk fabrics dyed in brilliant colors

- Spice merchants filled the air with aromatic scents

Today, walking down the empty Hampi Bazaar street, with its ruined pavilions and scattered architectural fragments, requires imagination to visualize its former glory. Yet the street’s scale and the uniformity of its planning remain impressive, demonstrating urban design principles that created functional, beautiful public spaces.

A small modern bazaar operates near the Virupaksha Temple, where shops sell religious items, souvenirs, and basic necessities to visitors and pilgrims. While modest compared to the ancient market, it maintains the street’s commercial tradition.

The Pinhole Camera Effect

One of the Virupaksha Temple’s most fascinating features is a natural optical phenomenon visible in one of its chambers. During certain times of day, sunlight passing through a small opening in the western wall projects an inverted image of the gopuram on the opposite wall—essentially creating a camera obscura or pinhole camera effect using the temple’s architecture.

This phenomenon demonstrates ancient architects’ understanding of optical principles. While likely discovered accidentally, its incorporation into temple design shows how builders blended scientific observation with religious architecture. Some scholars suggest this inverted image held symbolic religious meaning, though interpretations vary.

The Royal Enclosure: Power and Grandeur

Southwest of the sacred center lies what archaeologists call the Royal Enclosure—the area containing the Vijayanagara Empire’s administrative and royal residential structures. While temples showcased religious devotion, the Royal Enclosure demonstrated political power, administrative capability, and royal luxury.

The Fortifications

The Royal Enclosure was protected by its own defensive walls with guarded gates, creating a citadel within the larger fortified city. These walls, though now partially ruined, still rise impressively in many sections, constructed from massive granite blocks fitted without mortar.

Guard rooms, watchtowers, and checkpoints controlled access to this restricted zone where the empire’s rulers lived and worked. Only authorized individuals—royalty, high officials, trusted guards, and necessary servants—could enter freely.

The Mahanavami Dibba (Platform of Victory)

The Royal Enclosure’s most prominent surviving structure is the Mahanavami Dibba, a massive square platform rising approximately 12 meters (40 feet) in three tiers. This impressive structure served as the empire’s most important ceremonial platform, where rulers displayed their power during major festivals and state occasions.

Function and Ceremonies: During the nine-day Mahanavami (Navaratri) festival celebrating the victory of goddess Durga over demons, the Vijayanagara rulers held elaborate celebrations atop this platform. Historical accounts from foreign travelers describe these spectacular ceremonies that included military parades with thousands of soldiers, hundreds of decorated elephants and horses, wrestling matches, music and dance performances, distribution of gifts to nobles and soldiers, and display of the empire’s wealth and military might.

The platform’s base and walls are covered with carved relief panels depicting these very celebrations—processions of elephants and horses, wrestling matches, hunting scenes, dancing girls, and royal ceremonies. These carvings provide a visual record of Vijayanagara court life and festivals.

The Stepped Tank (Pushkarani)

Within the Royal Enclosure sits an impressive stepped tank approximately 22 meters square and 7 meters deep. This geometric water reservoir features symmetrically arranged steps on all four sides descending to the water level, with small chambers built into the walls. The tank’s architectural sophistication demonstrates the empire’s advanced hydraulic engineering—it was fed by an elaborate system of underground channels that brought water from distant sources and maintained year-round supply even during dry seasons.

The Lotus Mahal

One of the Royal Enclosure’s most beautiful and well-preserved structures is the Lotus Mahal, a two-story pavilion that blends Hindu and Islamic architectural styles. The building’s name comes from its lotus-bud-shaped arches and domed towers that resemble opening lotus flowers.

The Lotus Mahal’s architecture is remarkable for its synthesis of different traditions—the arched openings and dome designs reflect Islamic influence, while the overall structure follows Hindu temple proportions and the decorative elements draw from both traditions. This architectural fusion reflects Vijayanagara’s cosmopolitan culture where Hindu rulers employed Muslim architects and craftsmen.

The building likely served as a recreational pavilion for royal women, providing a cool, airy space with excellent cross-ventilation design that channeled breezes through the structure, making it comfortable even during hot Karnataka summers.

The Queen’s Bath

Despite its modest name, the Queen’s Bath is an impressive structure—a large rectangular building enclosing a massive pool approximately 15 meters by 2 meters. The bath’s exterior appears relatively plain, but the interior reveals extraordinary sophistication with arched corridors surrounding the pool, ornate balconies overlooking the water, and an elaborate water supply and drainage system.

The architectural design ensured privacy for royal women while providing natural ventilation and light. Water was heated using an ingenious system before being released into the pool. After bathing, the used water drained through underground channels into surrounding gardens, irrigating plants—a sustainable water-use system that modern architects admire.

The Elephant Stables

Perhaps the most charming structure in the Royal Enclosure area is the Elephant Stables—a long symmetrical building featuring eleven large chambers with domed roofs, each designed to house a royal elephant. The building showcases yet another architectural fusion, with Islamic-style domes and arches combined with Hindu decorative elements.

Each chamber is spacious enough for an elephant to turn around comfortably, with high ceilings providing ventilation. The central chamber is larger and more ornately decorated than others, likely reserved for the most important tusker—possibly the emperor’s personal elephant.

The elephant stables’ excellent state of preservation allows visitors to easily imagine how these magnificent structures functioned during Vijayanagara times.

Practical Guide to Visiting Hampi Ruins

Best Time to Visit Hampi

October to February (Winter – Best Season): This period offers ideal conditions for exploring the Hampi ruins. Temperatures range from 15°C to 30°C, making outdoor exploration comfortable. The cooler weather is perfect for spending hours walking among monuments, climbing hills for sunrise or sunset views, and cycling around the extensive site.

The winter months coincide with several cultural events:

- Hampi Utsav (November): A three-day cultural festival featuring traditional music, dance performances, puppet shows, and light-and-sound programs at various monuments. This government-organized event attracts thousands of visitors and showcases Karnataka’s rich cultural heritage.

- Vijayanagara Festival: Celebrating the empire’s glory with cultural programs and historical reenactments

Disadvantages: This is peak tourist season, so expect larger crowds at major monuments and higher accommodation prices. Book hotels and transportation well in advance.

March to May (Summer): Summer in Hampi is brutally hot, with temperatures regularly exceeding 40°C (104°F). The harsh sun reflecting off granite boulders and light-colored monuments makes daytime exploration exhausting and potentially dangerous.

Advantages: Far fewer tourists, significantly lower accommodation rates, and a more authentic local experience. If you can handle heat, you’ll have monuments almost to yourself.

Strategy if visiting in summer: Explore monuments early morning (6-10 AM) and late evening (4-7 PM). Rest during midday hours (10 AM-4 PM) in air-conditioned accommodations or shaded cafes. Carry plenty of water, wear sun protection, and don’t underestimate the heat’s impact.

June to September (Monsoon): Hampi receives moderate rainfall during monsoon, transforming the usually arid landscape into lush greenery. Temperatures drop to comfortable levels (25-35°C), and the dust that usually pervades the site settles.

Advantages: Beautiful green scenery, fewer tourists, comfortable temperatures, and dramatic cloudy skies creating atmospheric photography conditions.

Disadvantages: Occasional heavy rains can disrupt outdoor exploration, some paths become muddy and slippery, and the Tungabhadra River swells, affecting coracle boat services. However, rain is typically not continuous—it comes in brief, intense bursts followed by clear periods.

How to Reach Hampi

By Air: The nearest airports are:

- Jindal Vijayanagar Airport (Vidyanagar), 40 km: This small airport operates limited flights from Bangalore and Hyderabad. From the airport, hire a taxi (₹800-1,200) or use app-based cabs to reach Hampi in 45-60 minutes.

- Hubli Airport, 165 km: Better connected with flights from major cities including Mumbai, Bangalore, Delhi, and Hyderabad. From Hubli, buses and taxis take 3-4 hours to reach Hampi (₹2,000-3,000 by taxi).

- Belgaum Airport, 270 km: Another option with reasonable connectivity, though farther than Hubli.

- Bangalore International Airport, 350 km: Most international and domestic travelers fly into Bangalore, then continue to Hampi by bus, train, or car—a 6-8 hour journey.

By Train: Hospet Junction (Station Code: HPT) is the nearest railway station, just 13 km from Hampi, with excellent connectivity to major Indian cities:

- From Bangalore: Multiple trains including the Hampi Express (ironic name given Hampi has no railway station)

- From Hyderabad: Direct trains available

- From Mumbai: Overnight trains via various routes

- From Goa: Direct trains operate regularly

From Hospet station, frequent local buses (₹20, 30 minutes) run to Hampi. Auto-rickshaws cost ₹150-200, and app-based cabs are available.

By Road: Hampi has excellent road connectivity:

- From Bangalore (350 km, 6-7 hours): Overnight buses (KSRTC state buses and private sleeper buses) cost ₹600-1,200 depending on comfort level

- From Goa (320 km, 7-8 hours): Regular buses and shared taxis available

- From Hyderabad (370 km, 7-8 hours): Multiple bus options and car rentals

- From Hospet (13 km, 30 minutes): Extremely frequent local buses and shared autos

Self-driving or renting a car/motorcycle from Bangalore, Goa, or Hyderabad offers flexibility to explore surrounding areas at your own pace.

Where to Stay

Accommodation options near the Hampi ruins suit all budgets:

Hampi Bazaar Area (Near Virupaksha Temple): This area puts you at the heart of the Hampi ruins, within walking distance of major monuments. However, as it’s the sacred zone, no alcohol is served, and most restaurants are vegetarian. Note that some guesthouses here face uncertain legal status due to heritage zone restrictions.

Budget: Basic guesthouses (₹400-800/night) – Temple View Guest House, Thilak Homestay, Srinivasa Homestay Mid-Range: Comfortable hotels (₹1,200-2,500/night) – Some properties offer rooftop restaurants with monument views

Virupapur Gaddi (Hippie Island – Across the River): This laid-back area across the Tungabhadra River attracts backpackers and long-term travelers with its relaxed atmosphere, riverside cafes, and social scene. Alcohol is available here unlike in Hampi Bazaar. Access requires crossing by coracle boat (₹20, 5 minutes).

Budget: Hostels and guesthouses (₹300-1,000/night) – Shanthi Guest House, Mowgli Guest House, Goan Corner Mid-Range: Better guesthouses with amenities (₹1,000-2,000/night)

Kamalapura: This small town 4 km from the Hampi ruins offers mid-range and upscale hotels with better facilities than Hampi Bazaar.

Mid-Range: Heritage Resort Hampi, Hotel Malligi (₹2,500-4,500/night) Upscale: Evolve Back Kamalapura (luxury heritage resort, ₹15,000+/night) – Features excellent facilities, swimming pool, and cultural programs

Hospet Town (13 km): The nearest city provides the widest range of accommodations, from budget lodges to comfortable hotels, plus better restaurants, shopping, and ATMs.

Budget: Numerous options (₹500-1,200/night) Mid-Range: Hotel Malligi, Clarks Inn (₹2,000-4,000/night)

Booking Tips:

- Book 1-2 months ahead for winter season (November-February)

- Prices increase during Hampi Utsav and major festivals

- Budget accommodations fill quickly—reserve even if you’re not picky about where you stay

- Read recent reviews carefully as quality varies significantly

- Confirm amenities like AC, hot water, and WiFi as not all properties provide them

Getting Around Hampi

The Hampi ruins spread across a vast area, making transportation essential:

Bicycles (Most Popular): Renting a bicycle is the ideal way to explore Hampi at your own pace. Rental shops near Hampi Bazaar and Virupapur Gaddi charge ₹50-100 per day. Cycling allows you to stop whenever something catches your interest, access places cars can’t reach, and enjoy the landscape intimately.

Disadvantages: Hampi’s terrain includes rough paths, steep climbs, and hot weather. Not suitable for those unfit or uncomfortable cycling. Some distant monuments require too much pedaling.

Motorcycles/Scooters: Renting a two-wheeler (₹400-600 per day) offers more range and comfort than bicycles. However, motorcycles aren’t allowed in some core heritage areas, and you’ll miss the intimate experience cycling provides.

Auto-Rickshaws: Hiring an auto-rickshaw for a full day (₹800-1,500 depending on distance and bargaining) provides comfortable transport with a driver who doubles as a basic guide. Suitable for families, elderly visitors, or those who prefer not to self-navigate.

Disadvantages: You’re constrained by the driver’s schedule and knowledge. Drivers sometimes rush you through sites or push commission-earning stops.

Walking: Several important monuments in Hampi Bazaar area are within walking distance—Virupaksha Temple, Hemakuta Hill temples, and the riverside path to Vittala Temple (2 km). Walking offers the most intimate experience but is impractical for covering the entire site.

Coracle Boats: These traditional round boats ferry people across the Tungabhadra River between Hampi Bazaar and Virupapur Gaddi (₹20 per person). The short ride itself is a delightful experience, and the boat operators skillfully navigate the current using long poles.

What to Bring

Essentials:

- Comfortable walking shoes with good grip (paths are rocky and uneven)

- Sun protection: High SPF sunscreen, sunglasses, wide-brimmed hat

- Light, breathable clothing (modest—cover shoulders and knees at temples)

- Reusable water bottle (stay constantly hydrated)

- Small backpack for day trips

- Cash in small denominations (many places don’t accept cards)

- Basic first-aid kit and any personal medications

For Photography:

- Camera with extra batteries and memory cards

- Wide-angle lens for landscapes and architecture

- Telephoto lens for detail shots

- Tripod (if you can manage carrying it)

- Lens cleaning cloth (dust is pervasive)

Optional but Useful:

- Torch/flashlight (some temples are dark inside)

- Foldable seat cushion (for resting on rocks)

- Snacks (food isn’t available everywhere)

- Power bank for phone/camera

- Light rain jacket during monsoon

Budget Planning

Daily Budget Estimates (Per Person):

Budget Travel (₹800-1,500/day):

- Accommodation: ₹400-800 (guesthouse/hostel)

- Food: ₹200-400 (local restaurants)

- Transport: ₹100-200 (bicycle rental, buses)

- Monuments: ₹100 (most are free; major sites charge ₹40/600 for Indians/foreigners)

Mid-Range Travel (₹2,500-4,500/day):

- Accommodation: ₹1,500-2,500 (comfortable hotel)

- Food: ₹500-1,000 (decent restaurants, cafes)

- Transport: ₹300-600 (scooter rental or hired auto)

- Monuments: ₹600 (foreign tourist rates)

Comfortable Travel (₹6,000+/day):

- Accommodation: ₹3,000-15,000+ (heritage resort)

- Food: ₹1,500-3,000 (resort dining, nice restaurants)

- Transport: ₹1,000+ (private car with driver)

- Guide fees: ₹500-1,000

Important Practical Tips

ATMs and Cash: Hampi has NO ATMs. Withdraw sufficient cash in Hospet, Kamalapura, or before leaving your origin city. Most restaurants and shops accept only cash. Some larger hotels accept cards, but don’t rely on it.

Mobile Network: Coverage is decent in main Hampi areas with Airtel, Jio, and Vodafone providing reasonable service. However, signal can be weak in remote monument areas. Download offline maps before exploring.

Food and Water: The water supply in Hampi is limited and not always safe to drink. Buy bottled water and avoid ice in drinks. Restaurants serve mostly South Indian vegetarian cuisine—dosas, idlis, rice meals. Some cafes in Virupapur Gaddi offer continental options. Food safety is generally good at established restaurants, but avoid street food if you have a sensitive stomach.

Dress Code: While Hampi has a relaxed atmosphere, remember you’re visiting religious sites. Cover shoulders and knees when entering temples. Remove shoes before entering temple areas. Modest dress shows respect and helps you avoid unwanted attention.

Guides: Official guides available at major monuments provide valuable historical context and point out details you’d otherwise miss. Rates are approximately ₹500-1,000 for 2-3 hours. Ensure your guide is certified and agree on fees before starting.

Health and Safety:

- The heat can be dangerous—don’t underestimate it. Rest in shade during peak hours

- Rocky terrain poses twisted ankle risks—watch your footing

- Monkeys near some temples can snatch food and belongings—don’t feed them and keep bags closed

- Climbing on monuments is prohibited and dangerous

- Swimming in the Tungabhadra River is not recommended due to currents and water quality

Environmental Responsibility: The Hampi ruins face serious littering problems. Please:

- Carry trash until you find proper bins

- Don’t leave plastic bottles or wrappers at monuments

- Avoid touching or climbing on fragile carvings

- Don’t write or carve on monuments (it’s illegal and damages heritage)

- Support local businesses and artisans rather than souvenir shops selling mass-produced items

Beyond the Ruins: Experiences in Hampi

Sunrise and Sunset Views

Matanga Hill (Best Sunrise): Wake before dawn and climb Matanga Hill (behind Virupaksha Temple, about 30 minutes climb) for Hampi’s most spectacular sunrise. As the sun rises, it paints the boulder-strewn landscape and distant monuments in golden light while mist rises from the Tungabhadra River valley—an unforgettable sight.

The hilltop features a small Veerabhadra Temple and offers 360-degree panoramic views of the entire Hampi ruins site. Arrive early as it’s a popular spot—the best viewing positions fill quickly.

Hemakuta Hill (Best Sunset): This hill near Virupaksha Temple is dotted with small temples and offers excellent sunset views. The advantage over Matanga Hill is easier access and multiple viewing spots. Watch the sun sink behind the boulder landscape as monuments glow in warm evening light.

Anjanadri Hill (Birthplace of Hanuman)

According to Hindu mythology, Anjanadri Hill is the birthplace of Lord Hanuman (the monkey god). The hill lies across the Tungabhadra River, requiring a 575-step climb to reach the hilltop temple. The climb is moderately challenging but rewarding with panoramic views and spiritual significance for devotees.

Many monkeys inhabit the area—bring offerings of fruit if you wish, but protect your belongings as these monkeys are bold thieves.

Sanapur Lake

This scenic lake about 5 km from Hampi offers a refreshing escape from monument hopping. The calm waters surrounded by boulder hills create picturesque scenery. Some visitors swim here (water quality and safety should be evaluated personally), and coracle boats are available for rides. The area has a relaxed atmosphere with small cafes serving snacks.

Boulder Climbing

Hampi’s unique boulder formations attract rock climbers from around the world. The granite provides excellent grip, and thousands of boulder problems of varying difficulty levels keep climbers engaged for weeks. Several guesthouses and cafes cater specifically to the climbing community.

If you’re a climber, bring your equipment. Rental options are limited. Even if you don’t climb, watching skilled climbers tackle challenging boulder problems is entertaining.

Coracle Rides on Tungabhadra

Beyond the utilitarian river crossings, longer coracle rides (₹100-300 per person depending on duration) let you explore the Tungabhadra River’s scenic stretches. Skilled boatmen navigate these round, bamboo-frame boats through currents, offering unique perspectives of riverside monuments and natural scenery.

Village Exploration

Rent a scooter and explore small villages surrounding Hampi—Anegundi, Hirebenakkal, and others. These villages offer glimpses of rural Karnataka life largely untouched by tourism. You’ll see traditional houses, agricultural activities, local temples, and friendly villagers curious about visitors. It’s a completely different experience from monument hopping and provides cultural context for understanding the region.

Conclusion: Why Hampi Ruins Deserve Your Time

The Hampi ruins offer something increasingly rare in our modern world—a chance to step completely outside contemporary reality and into a landscape where history, spirituality, natural beauty, and human achievement converge in extraordinary ways.

Standing among these monuments, you’re not just looking at old buildings—you’re connecting with human stories spanning centuries. Every carved pillar was shaped by an artisan’s hands. Every temple hosted prayers and celebrations. Every palace chamber witnessed royal intrigues and decisions that shaped kingdoms. The massive fortification walls defended against real armies. The irrigation channels watered actual fields that fed hundreds of thousands of people. The marketplace streets bustled with merchants from across the known world.

The Hampi ruins prove that India’s historical and cultural heritage extends far beyond the handful of famous monuments that dominate tourist itineraries. While everyone visits the Taj Mahal, relatively few explore Hampi—yet this UNESCO site arguably offers a richer, more immersive historical experience. You can spend days here and still discover new temples, hidden corners, and fascinating details.

What makes Hampi special is the combination of elements: the spectacular boulder landscape that seems designed by nature specifically to host these ruins, the sheer scale of the archaeological site allowing you to wander for hours without seeing everyone, the remarkable preservation of so many structures despite centuries of abandonment, and the layers of history visible everywhere—from ancient pre-Vijayanagara shrines to Islamic architectural influences to traces of the catastrophic destruction in 1565.

For history enthusiasts, Hampi provides endless fascination—the opportunity to trace the rise and fall of one of Asia’s greatest empires through tangible remains. For architecture lovers, the monuments showcase the pinnacle of Dravidian temple architecture and demonstrate sophisticated engineering principles. For photographers, the combination of dramatic landscapes, intricate carvings, and atmospheric light creates perfect conditions. For spiritual seekers, the continuing religious traditions at Virupaksha Temple and the sacred geography mentioned in ancient texts provide authentic connection to India’s living spiritual heritage.

Even if you’re none of these—if you’re simply a curious traveler wanting to see something different, something that will challenge and expand your perspective—Hampi delivers. It’s a place that rewards slow, contemplative exploration. The more time you spend wandering among the ruins, cycling through the landscape, watching sunset from hillsides, and absorbing the atmosphere, the more Hampi reveals itself to you.

The Hampi ruins remind us that all civilizations, no matter how powerful or wealthy, are temporary. The Vijayanagara Empire ruled for over two centuries, amassed incredible wealth, built magnificent monuments, and created sophisticated urban infrastructure—yet within six months of military defeat, its capital lay in ruins. This impermanence isn’t cause for despair but for reflection on what truly matters—the art, architecture, and cultural achievements that survive to inspire future generations long after empires have fallen.

As you explore Hampi, you’re not just a tourist visiting dead monuments. You’re a link in a chain of human experience that stretches back centuries and will continue forward. The same sun that rises over Matanga Hill illuminated Krishnadevaraya’s victory parades. The same Tungabhadra River that you cross in coracle boats sustained the ancient city. The same granite boulders that amaze you today witnessed the empire’s glory and its fall. You’re walking in footsteps worn smooth by thousands of years of pilgrims, merchants, soldiers, artists, and travelers—all drawn to this special place where landscape, history, and spirituality intertwine.

The Hampi ruins await your discovery. Will you answer their call?